How Scope 2 Revisions Can Open the Door for Corporate Investment in Tribal Clean Energy

By Whitner Chase, Senior Manager, Seneca Environmental

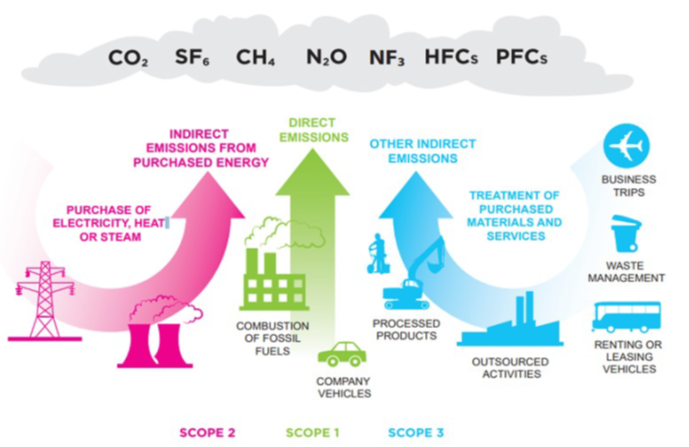

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol is the world’s most widely used framework for corporate greenhouse gas accounting, and its Scope 2 guidance is the primary set of rules for quantifying an organization’s emissions from purchased electricity. That includes electricity purchased through contractual instruments like renewable energy certificates (RECs). This guidance is currently being revised through a formal process; the latest public comment period closed on January 31. How the Protocol’s final revisions define eligible REC procurement will drive important changes in the market: what corporate buyers can credibly procure, what developers can finance, and which communities see investment and associated benefits.

The “deliverability” requirement in the current draft Scope 2 revisions has the admirable intent of improving the accuracy and credibility of RECs in corporate carbon accounting. But this requirement, especially as it’s tied to geographic constraints, would make REC sales more difficult for Native Nations.

Tribal lands have substantial renewable energy development potential — more than the average U.S. acre, according to a federal study. But while a number of tribally owned renewable energy projects have been coming online in recent years, the participation of Native Nations in the energy transition has been constrained despite clear climate and community benefits. Many Native communities are in rural or remote areas, where the default energy market model often fails to support project development. Because projects there face higher supply chain costs, thinner technical expertise in the workforce, costlier interconnection buildouts, and other barriers, private capital tends to flow elsewhere unless impact investors, philanthropy, or public programs close the gap.

A fundamental truth of the REC market is that electricity cannot be physically traced between meters on interconnected grids, so any “100% renewable” claims are simply contractual/accounting claims unless the load is supplied by behind-the-meter resources. Because of this reality, all but the strictest deliverability rules would not guarantee the physical alignment of RECs with purchasers’ energy demand.

The deliverability requirement in the current protocol draft would narrow eligible procurement options for corporate buyers, focusing energy and REC purchasing on regions with high levels of economic activity and easier procurement pathways. This would reduce demand for renewable energy development on Native lands and in other rural communities where decarbonization is most urgent from an environmental justice perspective. If the deliverability requirement narrows corporate energy procurement options, it will also narrow which communities receive investment.

A significant portion of U.S. RECs are sourced from facilities in Texas’s ERCOT grid, where RECs are most affordable thanks to strong market conditions for renewables development and the lack of a state renewables portfolio standard. The Scope 2 changes should lower demand for ERCOT RECs and reallocate that demand to other grid areas, ideally driving more renewable energy development in those regions. We generally support a diversification of demand, but we are concerned about the unintended effect on Native Nations hoping to attract renewable energy investment capital. Our research indicates that there are at least 30 megawatts of installed renewable energy capacity across dozens of projects owned by Native Nations that are currently not utilizing their RECs. Those RECs are available now from existing projects, which will allow Native Nations to maintain and decommission or repower those projects. RECs can help bring many more megawatts online, provided that they can attract corporate virtual power purchase agreement (VPPA) or REC-only contractual investments.

Seneca Environmental is positioned to finally bring this value to market through our work as a REC aggregator/dealer and tribal owner’s representative to energy buyers. These plans, already at risk due to political and economic realities, would suffer further from a stricter deliverability requirement, as most REC buyers don’t have load in the same region as Native communities. Therefore, those buyers would not look to tribal projects in those regions to meet the requirement proposed in the current Scope 2 draft.

The opportunity to support tribal renewable energy is more accessible than ever. But we’ve heard far too often from corporate buyers that their appetite for tribal REC investment is dependent on the final outcome of the Scope 2 revisions. Therefore, it’s critical that the Scope 2 revisions take steps to encourage tribal energy procurement.

The key is to avoid turning Scope 2 into a geography gatekeeper and build an even more impact-aware accounting standard — one that maintains integrity by letting companies direct procurement toward the grids and communities where marginal decarbonization and resilience gains are greatest. There are issues with the consequential accounting method being drafted alongside the Scope 2 revisions, particularly the verification of “additionality” claims; we believe it is unlikely that consequential accounting will become mainstream in its current form, so we don’t believe at this point that it should represent a solution.

Accounting rules like the Greenhouse Gas Protocol don’t just shape disclosures: they shape the cost of capital. When Scope 2 criteria effectively determine which RECs offer value to buyers, they also determine which revenue streams feel predictable enough to underwrite financing. An equitable Scope 2 revision can help transform today’s patchwork of grants and one-off philanthropic support into a more financeable, repeatable pipeline of tribal renewable energy projects, because it would make long-term tribal REC demand more bankable to both buyers and lenders.

Our vision is straightforward: Scope 2 should keep clear inventory boundaries, but it should not restrict climate action to only the reporter’s physical grid connection. We feel that a national inventory boundary is sufficient for the United States. If promoting equity in energy procurement while closing greenwashing loopholes is an aim of the Scope 2 Technical Working Group (as we believe it should be), the next draft should consider a system where reporting entities are rewarded for purchasing RECS from grid areas with a high carbon intensity, which describes most tribal utility territories.

There is no perfect way to quantify an organization’s emissions from purchased electricity; each method has its tradeoffs, but Native communities should not be left behind (again) in the name of progress.